The Ute Indians were a nomadic tribe who made their summer home in the area that is now western Colorado. They are believed to have first appeared as a distinct people in AD 1000–1200 in the southern part of the Great Basin, an area roughly located in eastern California and southern Nevada. The Ute people migrated to the Four Corners region by 1300, from where they continued to disperse across Colorado’s Rocky Mountains over the next two centuries. By the early seventeenth century, Nuche territory included portions of the Great Basin, the Colorado Plateau, and the Central and Southern Rockies. This extensive area was inhabited by a population estimated at upwards of 5,000–10,000, although lower population levels may be more likely. While a definitive listing of Ute bands is made difficult by their fluid membership and high mobility, a loose confederation of thirteen bands was in place by the seventeenth century. It included seven eastern bands with ranges primarily in present-day Colorado and six western bands in present-day Utah. The eastern bands included the Yampa, Parianuche, Sabuagan, Tabeguache, Weeminuche, Capote, and Muache, and the western bands were the Uintah, Timpanogots, Pahvant, Sanpits, Seuvarits, and Moanunts.

The Utes were skilled hunters and gatherers, relying on the abundant natural resources of the region for their subsistence. They hunted deer, elk, and bighorn sheep, and gathered a variety of plants, including berries, nuts, and roots. The Utes also traded with other tribes, exchanging goods such as furs, hides, and baskets.

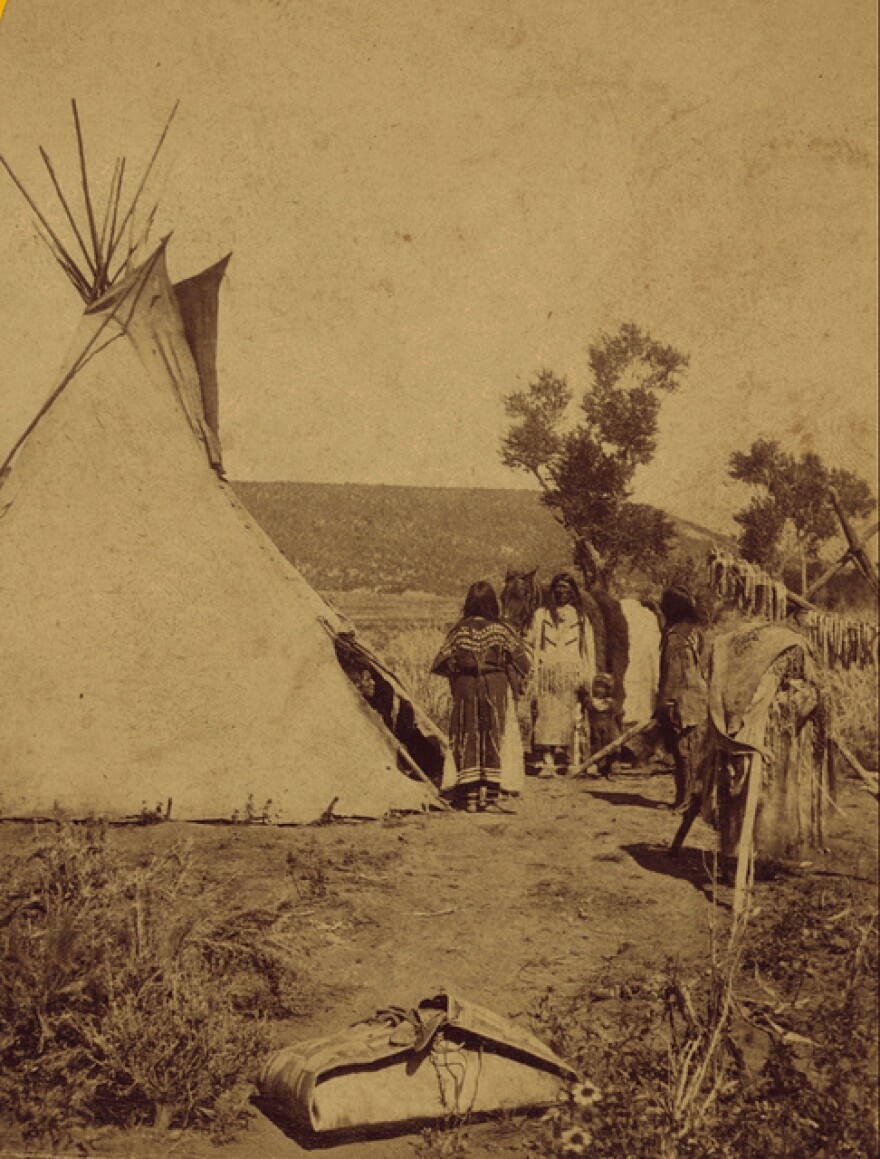

The Ute were one of the first Native American tribes to acquire horses. According to tribal historians, the Utes acquired horses as early as the 1580s, while other sources suggest that Ute captives escaping from the Spanish in Santa Fe fled, taking with them Spanish horses, around 1637. The horse became a vital component of everyday life for the Ute community. With the horse, they could transport larger items over long distances, travel farther and more quickly, and raid neighboring communities to obtain slaves and goods, which were later traded for more horses. The Utes began to adopt many aspects of Plains Indian culture, living in mobile tipis and hunting buffalo, elk, and deer over long distances. The horse facilitated Ute raiding and trading, making them respected warriors and important middlemen in the southwestern slave and horse trade.

Buckskin Charlie

Southern Ute tribe in Boulder, Colorado. Buckskin Charlie, top row 4th from right.

Buckskin Charlie, also known as Sapiah, was the preeminent chief of the Mouache band of the Southern Ute Tribe beginning around 1870. He was born to a Mouache father and an Apache mother, perhaps in the vicinity of Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico. The origins of his English name, “Buckskin Charlie,” are obscure, and later in life he was also referred to as Charles Buck. Buckskin Charlie was a respected leader and diplomat who worked to maintain peace between the Utes and the white settlers who were encroaching on their land. He was recognized as Chief of the Mouache and Servero Bands and Principal Chief of the Capote. He succeeded Chief Ouray as the official treaty negotiator and learned English to better communicate with the white settlers. Buckskin Charlie was also a skilled horseman and warrior. He led the rescue of women and children who were abducted during the Meeker Massacre and was given the Rutherford Hayes Indian Peace Medal by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890. He rode with Geronimo in Theodore Roosevelt’s 1905 Inaugural Parade. Buckskin Charlie was a beloved figure among the Ute people and is remembered for his leadership, diplomacy, and courage. His son, Antonio Buck Sr., succeeded him as hereditary chief and became the first elected chairman of the Southern Ute tribe.